Maurice Crosland, "Popular science and the arts : challenges to cultural authority in France under the Second Empire:" (1)

The Popularization of Science

The period of the Second Empire (1852–70) was one of exceptional change and rapid economic growth. It was then that France, previously well behind neighbouring Britain in the construction of railways, underwent a determined programme of railway building. The

period has an arguable claim to be that of the long-postponed industr1ial revolution in France, something which had begun in Britain in the previous century. . . .

It was also a period of striking cultural change and innovation. This is demonstrably true of literature, art and music. It is equally true of one aspect of science. Perhaps the spirit of realism in the arts from the 1850s was more consonant with science than the previous fashion of Hippolyte Taine, probably the most distinguished thinker in the France of the Second Empire, saw the ‘reigning [intellectual] model ’ in his country changing over time. In the seventeenth century it had been the ‘ honnéte homme ’ [cultivated gentleman], in the eighteenth the philosophe [rational thinker], and in the early nineteenth, the romantic poet. In the second half of the century the new hero was to be the savant in the new sense of the scientist. He himself sought to bring philosophy, literature, history and

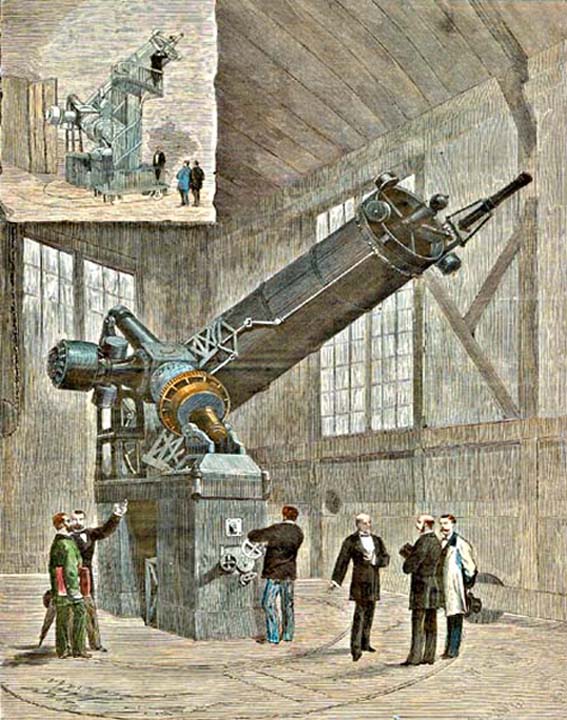

New Telescope at Paris Observatory, Monde illustre (Sept 1875)

art within the spirit of experimental science. Yet the argument to be developed here is less that mainstream science was dominant than that a new activity, the popularization of science, had arrived in a big way and in a way not divorced from literature. Of course the popularization of science did not start in the nineteenth century. Earlier attempts had been made, for example, to explain some of Newton’s work, but there was no regular commitment to keep the general public informed about the broad sweep of scientific activity until the mid-nineteenth century, when several journals were founded to present aspects of science and technology regularly to a wider public. A new career was opening : that of popularizer of science and science writer. . .

. . . the profession of science in France had emerged in the wake of the French Revolution of 1789. The contrast between professionalism in science in the early nineteenth century is nowhere more marked than in a comparison of the Paris Académie des sciences and the Royal Society of London, still at this time a proud heir to the British amateur tradition. The main point at issue is that in France science was something of an elite activity, related already to national university examinations and policed at its higher levels by the Académie des sciences. . . .

We may conclude that in the French situation there was a special need for popularization. The Académie jealously guarded its privileges and frowned on any of its own members who may have wanted to bridge the gulf between the elite and ordinary people. . . .

[In the mid-19th century] there occurred an innovation in the history of French newspapers. Emile de Girardin, the proprietor of a pioneering liberal daily newspaper, La Presse, realized that he could make a substantial reduction in the price of newspapers if he included a large number of advertisements. But in addition to increasing the circulation of his newspaper by halving the price he also increased the circulation by making the contentsof more genera1 interest. Restrictions under Napoleon III on discussion of political matters in newspapers indirectly encouraged the public discussion of other matters. Each day the bottom third of the large front page of La Presse was usually occupied by what was called the feuilleton. This section would often be devoted to the arts, with reviews of plays and operas currently being performed on the Paris stage. Girardin also signed up novelists including George Sand and Honore’ de Balzac to serialize their latest productions. In the nineteenth century it became common for novels to appear first in serial form in a newspaper before being published in book form.

Girardin recognized the increasingly important part that science was playing in France and wanted this to be reflected in his newspaper. Accordingly one day every week the feuilleton was devoted to science. It would be part of the duties of one of the reporters to write an article which usually consisted in the early days of a fairly straightforward account of the recent proceedings of the Académie des sciences. Apart from memoirs read, these meetings were often a rich source of scientific news, since the Académie was not only a national centre for the reporting of research but also the recipient of international scientific developments. . . .

Another aspect of popularization is the potential size of its readership. At the highest level science, as presented to the Académie, was reported in its weekly Comptes rendus [reports] , of which several hundred copies were printed. The key journal of the physical sciences, the Annales de chimie et de physique had only a slightly greater circulation. But the popularizers had a readership of thousands, if not tens of thousands. What they wrote could influence the attitude of the general public not only towards science and technology but also towards the Académie and individual Academicians, whose research might be reported and commented upon. They were, therefore, looked upon by the Académie with increasing unease. Although at first the popularizers were largely ignored, the Académie came to realize that it too had to make some contact with a wider public. In the second half of the century more Academicians began to make some contribution to popular science, whether by public lectures, such as the Soiréss de la Sorbonne [Evenings at the Sorbonne] or by the printed word. Yet even then some Academicians, with traditional caution, preferred to publish anonymously. . . .